Arts

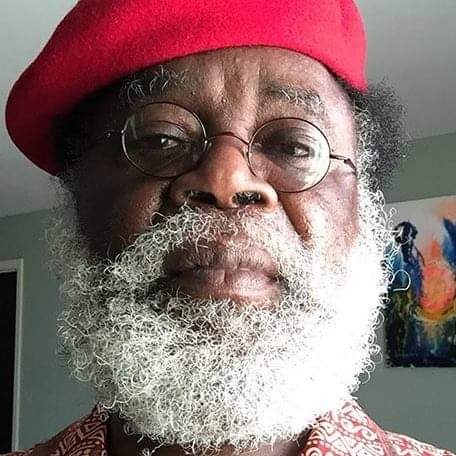

75th birthday: dele jegede, the total artist

One afternoon in 1959, Omodele paid me a visit at my home in Ule Asa, Odo Oja, Ukere Ekiti. (We were both from the same part of town, and our respective family houses a mere stone throw from each other). As soon as he took his seat, he saw my younger brother, then a late toddler, greeted him warmly, and told him to pose for a graphic portrait. He asked for a pencil and a sheet from my 2D exercise book, steadied himself in his seat, and instructed my brother to stand fairly close to the window where his face could benefit from the generous light from the cloudless sky. He went to work, his penetrating gaze moving back and forth from the wondering subject a few feet from that gaze and the piece of paper on which he was assiduously trying to reproduce his image. Sole witness to this epiphany and in utter wonderment, I watched Omodele wield the pencil with a near-miraculous ease, his inchoate, tentative lines coalescing into recognizable forms: a nose, two eyes, two ears, a mouth whose lips were in a state of half-smile and partial closure. I savoured– or eavesdropped – the creative, conspiratorial rasp issuing from the dialogue between pencil and paper as the artist realized the vertical stripes on his subject’s shirt. I watched as the artist straightened up from his bending posture, touched his lips with the tip of the pencil, took another look at the subject of his inspiration and compared what he saw with his re-presentation on paper. The artist then invited his ‘model’ to take a look at his new image, and the young boy responded in a wonder without/beyond words.

Beyond words. My mother took a look at the new portrait, gasped, and exclaimed ‘Hee, ooomoomo gun o’ (Wonderful; this artist’s hand is perfect). When father returned from the farm and was shown the portrait, his response was equally appreciative (O modaa o; isenida bi foto. (Oh, this is beautiful; it looks like a photograph). This portrait remained part of the family heirloom for a long time, and my father never stopped referring to awe re olooara (your friend with the artistic hand) each time his inquiry fell on Omodele.

If my parents were surprised at Omodele’s artistic feat/ talent, my own feeling was a combination of awe and astonishment. And a healthy dose of admiration. For, the question that kept popping up in my mind is: where did Omodele learn his art? Who taught him? What Angel sprinkled this miraculous flair on his pillow at night, tutored his hands, and fortified him with talents beyond the ordinary? I had every reason for asking these questions. For Omodele and I attended the same St. Luke’s Anglican Primary School at Uro, Ukere, a well organized and modestly provisioned school where the Christian Scriptures, were taught daily, English and Arithmetic virtually every day, and Yoruba, our mother tongue, was dubbed ‘vernacular’ and accorded a brief mention once or twice a week in the upper classes. Art, the teaching, creation, and appreciation of it, never had any noticeable place in the curriculum, though we had a weekly class called ‘Handwork’, an omnibus session for all kinds of ‘work’ from basket-making to a random play with clay-moulding.

Although we lived in a town where blacksmiths, carvers, body-beautifiers/decorators, drummers, singers, dancers, and incredibly imaginative festivals abounded, none of these creative agents was permitted to shed their impact on the school curriculum. As a matter of fact, the indigenous festivals were considered heathen practices and condemned as barbaric obstacles on that straight and narrow way that led to the Christian paradise. In spite of all this, where then did Omodele get the fire that propelled his imagination? Who were his models so early in life? Who were his silent teachers? How did a country boy whose artistic career began on such fortuitous grounds turn out to become one of Nigeria’s most original, most versatile, and most conscientious artists and art teachers?

There is yet another side to the versatility of this artist that is not known to the ordinary world: his powerful singing voice and dramatic/acting prowess. As far as the cultivation and showcasing of the talents in this capacity are concerned, St. Luke’s did a memorable job. For it was here I saw Omodele on the stage for the first time, under the directorship of the tirelessly creative, amazingly intriguing, and unforgettably inspiring Mr. Olatona. The year was 1958, Omodele’s final year in primary school. Early that year, as part of the activities marking the Health Week Programme in Ikere, St. Luke’s School presented the play, Omo Alaigboran (The Disobedient Boy), to a large gathering of townspeople, at the Holy Trinity Primary School, Odo Oja, right in the centre of Ikere township. Omodele played Omo Alaigboran, the main role in this play, and did so with a spirited verve and virtuosity that got many people in the audience asking with envious curiosity: omoi see yi? (Whose son is this?). The young actor earned the credit as a star, Mr. Olatona the recognition as a great teacher, and St. Luke’s its laurels as one of Ikere’s distinguished schools. I was a grateful member of the audience, and the resonance of Omodele’s powerful voice excites me to this day! Any wonder, then, that later that year,when Mr. Olatona selected the cast for the annual end-of-year play, for which he was famous throughout Ikere, Omodele again came up as the star actor. The play this time, was Jacob and Esau, based on one of the popular stories from the Bible’s Old Testament.With Omodele as Jacob and Ebenezer Babatope Ojo (another honey-throated singer – and personal friend) as Esau, Mr. Olatona orchestrated a virtuoso performance which the town remembered for many years after. Again, I was a fortunate member of the audience of that play in December 1958; and I must confess that this amazing duo’s sterling performance provided part of the inspiration for my own star role in our school drama the following year, in the same school, and directed by the same Mr. Olatona.

With the St. Luke’s phase over, Omodele stayed on briefly in Ikere before moving on to Lagos where he worked and lived by his art, then on to Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, where he honed his creative hunch and roared out of the undergraduate cadre with a widely acclaimed First Class degree. From that time on, the world became his stage, the sky his canvas, the sea his pot of paint, and ideas the rippling population of his thronged universe….

From Dele Jegede to dele jegede: daring, dissonance, and dissent

The foregoing biographical narrative (brutally brief though it is) justifies its telling by its own significance. For it provides one or two helpful revelations about jegede’s childhood years that most people do not know and about which he has been silent all these decades because of his decency and self-effacing modesty. The phenomenon now famously known as dele jegede is by no means an accidental artist who happened upon creative prodigy in his adult years, or one bearded nerd who discovered his artistic calling in the stuffy catacombs of university studios. Starting out as a spontaneous, natural artist, singer, actor, dancer, and verbal aficionado, nurtured by the profoundly vibrant, diverse, and inspiring culture of Ukere in the pre-Independence, pre-Pentecostal days, he has had, right from the early years, all it takes to be a total artist. The seeds were there, raw and ready, awaiting germination, growth, fruition, maturation, and harvest. Here is the origin of the music of jegede’s Muse: that flow to the splash of his paint that reminds us of the melody of his voice; that unique lyricism of his lines; that ineluctable vitality of the characters in his cartoons that brings intimations of stage presence and enactive possibilities; that unsettling eloquence in the dialogue of those cartoons that parallels their author’s public/political interventions. We are forcibly confronted with the creed and calling of the Artist as Public Intellectual.

And what an artist, what an intellectual dele jegede has turned out to be in the past 50 years! Raised and rooted in Yoruba culture whose aesthetic principle is based on a symbiotic relationship between ewa (beauty) and iwulo (usefulness), jegede’s art is the kind which connects and contests, which condemns and commends, which adds and subtracts. Idle beauty, facile prettiness, and sterile attitudinizing and other rigidly formalist encumbrances may have a place in certain climes and certain times, but jegede’s charge is the kind of art which is and does; the type whose terrible beauty(to borrow W.B. Yeats’s unparaphrasable phrase) arrests and liberates, repels and attracts; the type whose ear is close to the pulse of humanity, whose consciousness draws its strength from the intelligence of the universe.

Arimadake (The one that cannot see/observe without talking/commenting), towncrier, and troubadour of the Fine Arts, jegede has rattled the world’s jungle of silence for several decades, enabling muted masses to come to voice, helping lamed Justice back to its puissant feet. From the theory of Art to its practice; from the closet to the marketplace, jegede’s art has been the kind that says the unsayable, the kind that tells the naked Emperor that he is walking the streets without clothes. In this philosophy of relevance and social answerability, he confronts us and our consciences with the kind of art that shocks and awes, the kind that makes sure we do not forget, very much in the league of other Nigerian academic artists and art educators such as the much-admired Obiora Udechukwu, the early OluOguibe, and Victor Ehikhamenor.

Thus, as amply illustrated in Art, Parody, and Politics: dele jegede’s creative activism, nigeria and the transnational space*, that magnum opus assiduously ‘curated’ and edited by aderonke adesanya and toyin falola, no major (or minor but significant) happening in the world in the past 40 years has escaped the creative-critical gaze and comment of dele jegede: Nigeria’s twin plague of electoral malpractices and military dictatorship; the IMF ‘conditionalities’ and the pauperization of the Nigerian people; crumbling educational system; epileptic power supply; the travails of Abuja, the country’s beleaguered capital city with its broken lineaments, the Niger Delta as the aching fingers of Nigeria’s swollen foot. On the continental level the hyphenated horrors of Rwanda-Burundi; on the African diaspora, Kwanzaa and the celebration of African memory; the bling-bling blast of hip hop; the ironic variation on the Obama Yes We Can. Then, One World with MacDonald’s yellow ‘M’ dominating its sole window in a manner which mocks the Globalization mantra and its peddlers! A pageant of images, pathetically unnerving, pitilessly funny, helpfully useful. . ..

But in addition to, and oftentimes beyond, these topical engagements are matters of deep cultural and mythological fascinations: Esu the complex deity and his confounding crossroads; Sango the King who hanged but did not hang; mystic peregrinations, ancestral spirits, and the supplication(s) so achingly needed to cleanse the Nigerian/global ‘anomie’. It is impossible for somebody like me to encounter these images in jegede’s works without remembering our common Ukere origin. The spirit of Olosunta and Oroole breathes through these paintings, as do the haunting ululations from the shrine of Orisagisa. When I behold jegede’s owl-eyed Masquerade, my inner voice shouts Ira orunkininkin (Spirit/Denizen of the Other World, utterly).

Oni Esi Dee De (The One who Came Last Year Has Come Again)

That Masquerade metaphor spills over to the discourse of the present exhibition. For the time-defying trajectory of dele jegede’s vision and works brings powerful memories of the song which both typified and announced the outing of one of my favourite Ikere masquerades:

Ori okal’oka (The cobra’s head is the cobra)

Aremojaajaa jo (Aremo, dance your dance)

Ori ere l’ere (The python’s head is the python)

Aremojaajaa jo (Aremo, dance your dance)

Oni esi dee de (The one who came last year has come again)

Aremojaajaa jo (Aremo, dance your dance)

Oni esi dee dee (The one who came last year has come again)

Aremojaajaa jo (Aremo, dance your dance)

Now, unlike other egingun (masquerades), Aremo came out alone in a shroud that was uniquely his, trailed by singing children and cheering adults. Unlike other egingun, he carried no whips, chanted no frightening incantations, nor ran through the streets like a bull cut loose from its tether. His exquisite dance swelled the ranks of his fans as the small gourds (urere in Ukere dialect) tied to his ankles produced a rattling sound which both dictated and blended with the melody coming from the crowd. His dance steps were intricate, his body rhythm a marvel to behold. But more than any other attribute, what distinguished Egigun Aremo was his capacity for ‘re-inventing’ his dance steps every year, his uncanny ability to impress his fans and followers differently season after season. What followed was a case of modulated predictability, varied regularity, movement without monotony.

These, precisely, are the attributes which tutor my reflexes as I watch, study, and ponder these new images from dele jegede, Oni Esi Dee de, unarguably one of the most versatile, most socially engaged and engaging artists Nigeria has ever seen. The artist who gave us those haunting images of an ecologically devastated Niger Delta, and topped them up with images of Abuja, the capital city in which ‘Things Fall apart’, yes, that artist is here again, this time, with stunning images of our displaced conscience.

Most of the images in this exhibition leap out of two broad themes with a wrenching cause-and-effect eventuality: The Boko Haram Mayhem and the Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) consequence. But trust dele jegede the inveterate punster (To expect dele jegede’s figurations without pun(s) is to imagine the Atlantic Ocean without salt). How can you have IDP (Internally Displaced Persons) without first being cursed with a gang of IDP (Internally Displaced Politicians), complemented by another IDP (Internally Displaced Police)? In all these, jegede goes from abstract signification to visual metaphorization. Take another look at the Internally Displaced Politician in this collection; the cynical resignation announced by his chin-resting-in-palm posture; the pathological yellowing of his eyes indicating his jaundiced vision; those two birds, the smaller one on his cap, the larger on his shoulder, both symbolizing the stupor and stupid immobility of the object on which they stand (birds hardly ever perch on moving, dynamic/active objects); the ‘dumbo’ closure of the mouth; the somewhat funereal darkness of his dress. . . With all these and the patented fedora cap, is anyone still wondering who this ‘Displaced Politician’ is, and the repercussions of his ‘displacement’ for the present Nigerian situation?

Most of the images in this exhibition leap out of two broad themes with a wrenching cause-and-effect eventuality: The Boko Haram Mayhem and the Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) consequence. But trust dele jegede the inveterate punster (To expect dele jegede’s figurations without pun(s) is to imagine the Atlantic Ocean without salt). How can you have IDP (Internally Displaced Persons) without first being cursed with a gang of IDP (Internally Displaced Politicians), complemented by another IDP (Internally Displaced Police)? In all these, jegede goes from abstract signification to visual metaphorization.

With the other IDP (Internally Displaced Police), Fela Anikulapo’s ‘Roforofo Fight’ takes on an additional, ominous meaning. Two policemen from different branches of the Force (as indicated by the difference in the color of their uniforms) are locked in a grim fight-to-finish. The enforcers of the Law are at each other’s throat. Those charged with the prevention and apprehension of chaos are themselves chaos personified. Who then is left to police the police? And as hinted by the use of contrastive lighting in the painting, all this is happening in broad daylight; the background a running splash of colors.

A land of Internally Displaced Leader (IDL) and Internally Displaced Law (IDL) (my own parallel acronyms to jegede’s) can only end up as a land of Internally Displaced Peace. Boko Haram thrives in the vacuum created by the absence of leadership and rule of law. And this exhibition confronts us with startling images of that Nigerian nightmare. Consider the image of that young tesbih-wielding lady(Boko Haram 3), her mouth agape from religious sloganeering, behind her the hell of conflagration and carnage. Next we have a frightening image of the master of the mayhem, masked, fully clad, with a rifle at the ready, his finger on the trigger(Boko Haram 1); and the frightened figuration of a woman, lost from shock, mouth wide-open in bewilderment and horror, totally traumatized, gaze fixed on the absolutely unspeakable (Boko Haram (BH #BBOG). Then enter the displaced in an eerily logical progression, first the man with an extraordinarily huge load on his head, his face indistinct, his neck shortened by his burden(IDP 3). In a typical dele jegede combination of ironic symbolization and mordant indictment, a miniature Nigerian flag is attached to this burden in its utterly damning conspicuousness. A country that should be our bliss has become our burden. With its interplay of dull white and dark grey, the image shows the carrier and his burden as if both were hewn out of a background rock. The image of this sole trudger is followed by that of a crowd of afflicted refugees women, men, children, a laden donkey, all plodding along under heavy burdens with the exception of an old man who brings up the rear(IDP, Internally Displaced Peoples 1). There is a twilight tinge to the setting of this painting, a dullness which mimics the somber situation of these displaced people and their murky future.

But as is always the case with dele jegede’s universe, this exhibition is replete with a multiplicity of images, a multiplicity of situations, a multiplicity of moods, a multiplicity of tones. No matter how dark the cloud, this artist always leaves room for a silver lining of laughter. If the Boko Haram images weigh us down with their plethora of grief and gore, there are other images in this exhibition which lift the soul, which tease our lightness of being. Take another look at Generation What: Selfie and those two wiry old men and their Selfie moment: the curious smile on the lips of the first man, the delighted smirk on the lips of the other, their infectious excitement, the youthful curiosity in their gaze, and you marvel at what modern technology has done to our ‘normal’, traditional notions about aging. These two men are not only young at heart; they are also rejuvenated by the power of the new smart device in their hands. Aren’t we left to wonder what self images reward the old men’s curiosity and what they are invited to make of the wrinkles of age? Whichever way we look at it, there is something infectious about the jovial disposition of these men, something life-affirming about their tenacity.

If Selfie invites us to a childlike fascination with innovation, Celestial Aesthetics levitates us to a firmament of brooding meditations and cosmic awe. There is so much in the interplay of flashy blue and deep orange in these paintings, something almost eschatological, that summons lurid intimations ‘Marriage of Heaven and Hell’ by William Blake, the great Early Romantic English poet/painter. The jagged hole in right flank of Celestial Aesthetics 2 looks like a cave or an abyss, some dark opening to a Great Unknown. There is a concrete abstractness to this series, a deceptively proximate distance, something much deeper, much more intimidating than what we have encountered so far in dele jegede’s oeuvre. Some ideational and stylistic changes seem to be taking place, some transitions of a fundamental kind. The artist admits this much in a recent personal/private communication with me:

The Celestial series accommodates my fascination with terminality and infinity. I have become quite absorbed with cosmic vastness—its inexhaustibility and prowess—since the sudden departure of Ayo, our beloved son, in 2011.

In this typically poetic testament, we are invited to ponder what life and its sundry vicissitudes are capable of doing to an artist’s thematic and stylistic orientations. Here dele jegede seems to be serving notice of the next phase in his artistic ‘peregrinations’. Just as well. Life’s autumnal phase is sometimes mellow with its own magic, vibrant with shifts and re-visionings. . . .

Oni esi dee de (The prodigy of yesterday is here again). Yes, dele jedede has invited us to yet another harvest from the garden of his fecund imagination. In its gripping visual poetry, Transitions probes the depth of our pain – without forgetting to remind us of the possibilities of our laughter. The Total Artist is at it, again, achingly relevant in his message and uncompromisingly felicitous in his style. It is impossible to leave this harvest feeling indifferent, or feeling the same.